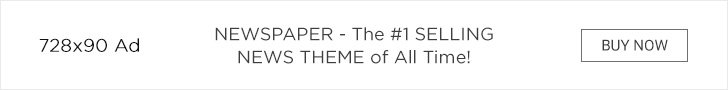

Timothy Bates tweets a 2010 meta-analysis showing that students who attend more classes also get higher grades:

These results suggest that attending more classes leads students to learn more and thus achieve higher grades. But there are some problems. First, class attendance is often used to grade students, trivializing the relationship. Second, the relationship is strongly confounded, as non-attendance is related to other unobserved student characteristics. What we want, then, is something more causally informative about time spent in class and learning. Fortunately, we have quite a few such studies.

The first type of study contemplates the extensions of school duration as a natural experiment. Cremieux tweeted one such study from Mexico recently:

This article estimates the effects of extending the school day during primary school on students’ educational outcomes later in life. The analysis is done in the context of a large-scale program introduced in 2007 that extended the school day from 4.5 to 8 ha in the metropolitan area of Mexico City. The identification strategy exploits cohort-by-cohort variation in full-time enrollment in primary schools. The results indicate that full-time elementary schools have positive and lasting effects on student achievement, raising high school entrance test scores by 4.8 percent of a standard deviation.. The effects are greater for women than for men. The difference in male and female effects of 2.1% of a standard deviation accounts for 16% of the gender gap on the high school entrance exam. In addition, full-time schooling decreases the likelihood of delays in completing schooling.

Thus, a huge increase of 3.5 hours per day leads to a small increase of 0.048 d, equivalent to 0.72 IQ.

In Denmark, a major school reform took place in 2014 which, among other things, extended the time students had to stay in school. The government commissioned a report on this, and found that this did not lead to changes in maths and Danish test scores:

The red line is public schools, the blue line is private schools. There is no change over time for any set.

In fact, it is difficult to find out how much longer they did school because the various sources on the reform do not say how many days the school days were before the reform, but asking the GPT4, we get these values:

-

After the reform (wikipedia): up to 3rd grade 30 hours/week, 4-6th grade 33 hours/week, 7-9th grade, 35 hours/week.

-

Before the reform (GPT4): “For lower grades (0-3rd grade), it was usually about 20-24 hours per week, and for older grades (7th-9th grade), about 25-28 hours per week .”

Thus, the extension was approximately 8 hours/week, or 1.6 hours/day. About half as drastic as the Mexican change, but produced no detectable effect. Of course, one could stand up and argue sleeping effects that might appear later when teachers have gotten used to the other parts of the reform, but don’t hold your breath. For more information about this Danish school reform, you can read Helmuth Nyborg and my 2020 Danish newspaper article (in Danish, of course).

Sweden also recently tried this approach with similar results:

The association SACO, Engineers of Sweden, has analyzed the state of knowledge in mathematics in primary, high school and adult education. The report compares, among other things, the grades of students who received an additional 330 hours of maths in elementary school with those of previous cohorts. Despite 37 percent more math hours, the overall grade point average among sixth graders is falling. At the same time, the association between higher grades and students with parents with higher education has strengthened over the period under review. In addition, the percentage of students who fail has increased.

I was able to find the Swedish relationship (Count or be counted), but doesn’t seem to add much of interest beyond the above summary. The decline in math scores is probably related to more foreigners in the younger cohorts, so the reform itself did nothing.

After writing these studies, I found that there an “Evidence for Learning” center, which has an online meta-analysis of these types of studies. I didn’t look at the details of the 70+ studies they list, but almost all of the larger ones show results like the above:

The Lee 2006 study is a study of Kindergarten students, so I assume it has teaching questions to the test, and of course regression to the mean will be applied.

Finally, school closures due to COVID-19 mean less time in school. Of course, there are other factors as well, but we could consider this a big exogenous shock. There is a meta-analysis of the effect size of this:

How much has school-age children’s learning progress slowed during the COVID-19 pandemic? A growing number of studies address this question, but results vary by context. Here we conduct a pre-registered systematic review, quality assessment and meta-analysis of 42 studies in 15 countries to assess the magnitude of learning deficits during the pandemic. We find a substantial global learning deficit (Cohen’s d = -0.14, 95% confidence interval -0.17 to -0.10), which emerged early in the pandemic and persists over time. Learning deficits are particularly significant among children from low socioeconomic backgrounds. They are also higher in math than in reading and in middle-income countries relative to high-income countries. There is a lack of evidence on learning progress during the pandemic in low-income countries. Future research should address this evidence gap and avoid the common risks of bias we identify.

That is, total disruption for weeks and sometimes months leads to a decline of only 0.14 d. This estimate is probably too high, since COVID-19 also had all kinds of effects that could affect learning, and because this meta-analysis includes several questionable studies from outside the developed world that show larger effect sizes ( as they always do).

These kinds of findings about school length in particular should be seen in the light of the large number of randomized controlled trials in education, that I received a meta-analysis from 2 years ago. The mean effect size for these is also very close to 0, only 0.06 d. Many of these involve more teaching hours, so it’s not all that unusual for large-scale studies of school reforms and COVID-19 closures to reach a similar conclusion: the number of teaching hours is not so important; what children bring from home is very important.

Of course, learning is just a matter of interest. People are really interested in increasing how much students learn because they know that learning lead to it statistically predicts other beneficial things later in life, such as income, longer lifespan, etc. So how about skipping the mediator and just looking at these results? Greg Clark and Neil Cummins already did this using 3 major UK reforms that extended compulsory schooling:

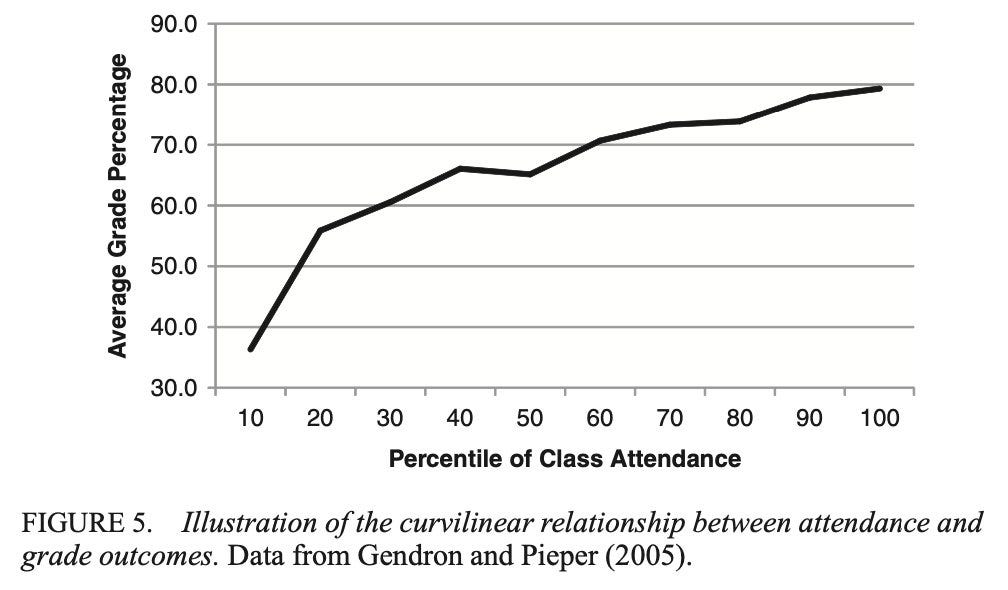

School and social outcomes are strongly correlated. But are these connections causal? Previous papers for England using compulsory schooling to identify causal effects have produced mixed results. Some found significant effects of schooling on adult longevity and earnings, others found no effect. Here we measure the consequences of extending compulsory schooling in England to ages 14, 15 and 16 in the years 1919–22, 1947 and 1972. Based on administrative data, these increases in compulsory schooling added 0.43, 0 .60 and 0.43 years of education in the affected cohort. . We estimate the effects of these increases in schooling for each cohort on measures of adult longevity, on housing values in 1999 (lifetime income index), and on the social characteristics of the places they go. affected cohorts die. Because we have access to all civil records, and a nearly complete sample of the 1999 electoral census, we find with great precision that all schooling expansions did not increase adult longevity (as previously found for expansions of 1947 and 1972), housing values or the social status of the communities where people die. Compulsory schooling from 14 to 16 had no effect, at cohort level, on social outcomes in England.

The longevity results are as follows:

Kids who were forced to stay an extra year in school didn’t live longer, and they didn’t end up with more expensive homes either:

These results are based on very, very large public datasets from the UK. So what was the use of these school extensions? Its effects are literally undetectable when analyzed in the most obvious way.

Going back to Timothy Bates’ initial tweet, we are now in a position to say that these results should definitely be no it should be interpreted as a demonstration that learning can easily be boosted just by adding more schooling. In fact, there is no easy way to boost learning. Everything has been tested. There are more resources on the Internet to learn from than ever before in human history, but general knowledge has not increased, and children and adults are no better at arithmetic. It is clear that the opportunity to learn is not an important variable in explaining the differences between people. And dare I say it never was?

From a cost-benefit perspective, more forced schooling for children means more teacher wages to pay. Since the effects of this on the actual learning of children seem to be between non-existent and minor, I suggest that this is not worth the price. School is a kind of child slavery. We threaten parents with fines if their children don’t show up to the labor camp where they are forced to listen to boring and often irrelevant stuff for years. When children are put to work, they are not doing anything really useful, they are doing mock work, which after a quick assessment will be thrown away. Sometimes they are also forced to do more at home. They are not paid for this work either. In fact, parents have to pay for it. It is clear that such a policy of slavery can only be justified on utilitarian grounds if the subsequent benefits of schooling are large. Previous research and all other evidence reviewed by Bryan Caplan in his The case against education, clearly show that schooling is not that useful by itself. Because of the high costs and low benefits, the cost-benefit analysis must be very negative. The question is just how much of compulsory schooling we should abolish.

Of course, some people will bite the bullet and say: the main function of the school is childcare. Great! This means we can easily lower the price. Taking care of the kids and making sure they don’t kill each other or each other is an easy job. It certainly doesn’t require a 4-year college degree. After all, parents already provide childcare themselves when schools are closed without this education.

Since people are asking, I should say that I am not literally advocating unschooling, usually called unschooling. I’m a moderate, maybe we can start by cutting forced schooling by 50% and see how that goes. That would only take us a few decades back in time in terms of politics.