That is the point: to be or not to be savages – Domingo Faustino Sarmiento

Just as the effectiveness of a warrior is diminished when his sword begins to rust, so too does the flesh of a Turk begin to rot when he assumes the lifestyle of an Iranian – Mahmud al-Kashghari

The struggle between civilization and barbarism – or oppression and freedom from another view – is as old as civilization itself. The big game hunter, the river fisherman, and the forest berry gatherer in the earlier ages of Man usually lived healthier lives than the sedentary farmers. Fighting over women and hunting grounds kept the population low, ensuring plentiful food could be obtained for relatively little work. There was some trade and there could be political hierarchies in the hunter-gatherer world, but the scale of both was seriously limited.

By contrast, farmers could scale their societies into the millions, but had to labor hard for their sustenance. Soil had to be manured, weeds pulled, animals warded off, water collected, crops harvested and threshed, chaff winnowed, and grain ground. Farming was a tedious and oppressive life – one that became more oppressive as agriculture improved. Storable food surpluses allowed for the rise of extractive social systems – warrior bands and chieftains arose to take plunder, tribute, or taxes depending on the contemporary social model. Nonetheless, the specialization that they allowed for caused both social and technological progress – even if it was slow and sometimes regressed.

Such progress led to periodic episodes of population growth which drove the expansion of civilization over the millennia. Sometimes the hunter-gatherers pushed the farmers back, sometimes they conquered the farmers and synthesized their material cultures, but usually they were overrun. By the Classical Age, the dividing line between civilization and barbarism had long since changed. Rather than farmers versus hunter-gatherers, it was between more advanced agricultural societies and either pastoralists or less advanced agricultural societies.

Herbivores are in the trophic level above plants as they have to consume food rather than creating their own. As such, calorie yields from crops are almost invariably higher than those of domesticated animals in most ecologies. Pastoralism is thus usually a worse use of land than agriculture.

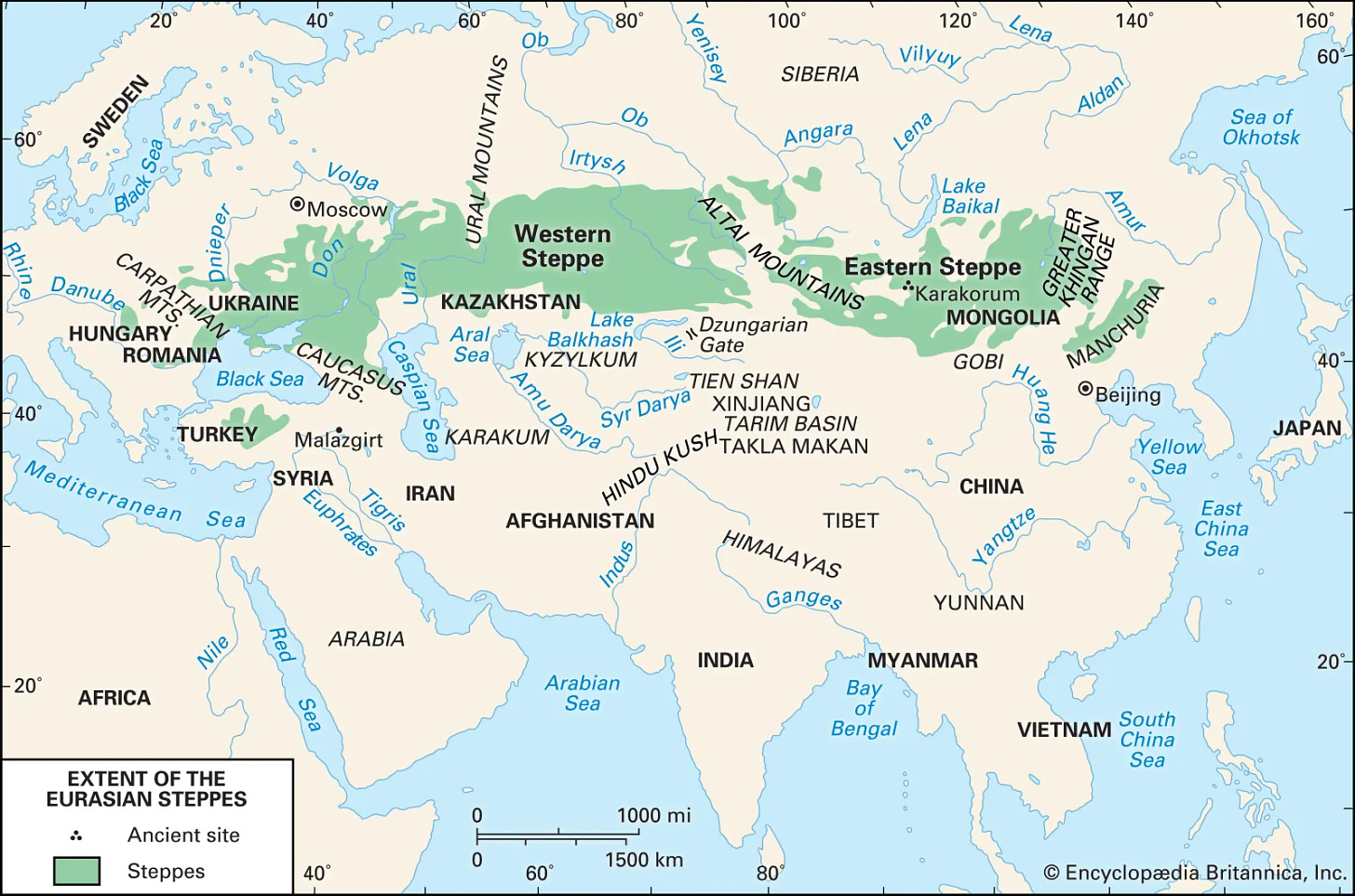

However, there were some ecologies where pastoralism was a better use of land than agriculture. The cold, windswept Eurasian steppe was hard on crops developed for the sunnier lands of the Middle East. It was also flat, offering few natural defenses from horse-riding raiders. Limited penetrations of the western steppe by sedentary peoples in the fourth and third millennia BC were decisively destroyed by the Indo-European nomads in what would begin a four-and-a-half thousand year pattern of barbarians pouring out of the steppe to devastate sedentary agricultural societies.

Elsewhere, it was more typical for land to be converted to pasture in the aftermath of depopulation or civilizational collapse. Hannibal’s devastation of Italy in the Second Punic War led not to recultivation of many of the depopulated areas, but instead conversion to pasture. The rich farmlands once cultivated by the Jesuits in Colombia regressed to pasture after their expulsion – the successors of the Jesuits there lacking the diligence to maintain the social and physical infrastructure essential for agricultural production.

Kindly consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my writing.

The destruction wrought by Chingis Khan and the wars of his successors devastated the physical infrastructure of agriculture in Iran and Central Asia. Dams were destroyed, canals blocked, and qanats collapsed. The population fell dramatically from the resulting famines – perhaps enough to cool the earth slightly. What were once developed farmlands became pastures or even deserts. Society was badly damaged as well. The old systems of Islamic law and order were swept away. In their place came a rapacious system of predation. Turko-Mongol nomads ruled and the Iranian peasants served. The barbarism of nomads had triumphed over sedentary and agricultural Perso-Islamic civilization.

That system (whose code was known interchangeably as yasa or törä) did possess virtues – loyalty and courage chief among them. The retainers of a Turko-Mongol lord were to be totally loyal to him – but also to be the beneficiaries of his largesse. Some of those retainers were hereditary servitors who were passed down from father to son through the originally Mongol institution of the keshik – essentially both a royal guard and cadre of high officials. Other retainers were recruited from the Cossacks – glorified brigands who had left the oppressions of ordinary life to live dangerously in the periphery (the famous Cossacks of Ukraine and Russia likely took their name from these eastern brigands).

Turko-Mongol lords gave lands and wealth to their retainers upon their triumphs – whether small raids or of the conquests of regions. With a weak or nonexistent state apparatus, often the only thing that a lord could do was redistribute plunder and grant swaths of lands away. The swaths of land given away were called “soyurghals” and were tax-free, ensuring the loyalty of military leaders but reducing the amount of land which could be taxed for the administration of the state.

Taxes under the Turko-Mongols in Central Asia were irregular, ensuring that state finances were weak. That in turn slowed reconstruction and development as well as encouraging rebellion or brigandage from unpaid soldiery. Many Turko-Mongol rulers, viewing their Iranian subjects with nothing but contempt, extorted them at will to make up for their financial shortcomings. In the process, they continued the long-term economic and demographic decline of their realms.

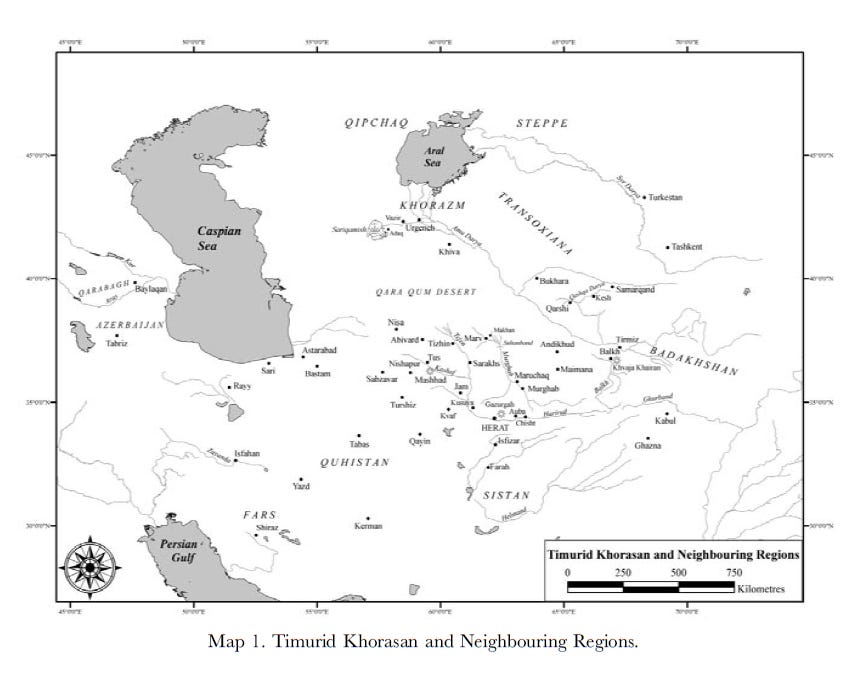

Following their solidifications of power, figures such as Shah Rukh and Sultan Husain Bayqara sought to reign in their unruly retainers. They wanted to develop their lands, regularize state finances, pay soldiers, and fund Islamic institutions that supported their legitimacy. The last was particularly relevant to Shah Rukh, who needed the help of Hanafi Sunni ulema to face the fanatical Hurufi heretics. Descended from barbarian warlords, the mid-to-late 15th century Timurid dynasts saw their new mission as civilizing their realm.

It was easier said than done. For example, Timurid ruler Sultan Husain Bayqara hired an Iranian, Khvaja Majd al-Din Muhammed Khvafi, from a noted family of bureaucrats to ensure that “…the peasant will prosper, the soldier will be content, and the treasury will be full”. Majd al-Din tried his best. Granted broad authority in reforming tax collection and fiscal administration, he was made equal in rank to the Turko-Mongol nobles who dominated the realm. He embarked on an initially successful program of bureaucratic and fiscal reform. Morally, the program was justified as a part of a return to Islam from the barbaric ways of the Turko-Mongols.

Majd al-Din’s successful efforts in improving state administration won him enemies among the Turko-Mongol nobility as his efforts undermined their influence. Bureaucratic rather than personal methods of state administration removed opportunities for corruption and also broke down the personal contacts which the nobility had with the ruler. The nobility, outraged by Majd al-Din’s infringement upon their power and influence, intrigued against him. He was successfully removed from office after seven years of service on charges of corruption. Powerful nobles such as the Turko-Mongol nobleman Alishir, prevented him from returning to office until 1487. By that point, the state fiscal crisis had reached such a point that reforms were unavoidable.

Following traditional Perso-Islamic ideals of justice, Majd al-Din was able to successfully reform the state in his second term in office. He opened up the soyurghal for taxation, regularized salary payments to soldiers and bureaucrats, and purged agents of the nobility on grounds of corruption. His successes in his second term in office again infuriated the Turko-Mongol nobility, who once again successfully intrigued against him. They brought him to trial – under a Mongol yarghu court rather than an Islamic sharia court.

Majd al-Din’s efforts at centralizing the very decentralized Timurid state were largely reversed after his second fall. Nobles refusal to allow Sultan Husain Bayqara’s tax collectors to travel to their lands and extensive corruption again left the treasury empty. Civilization had to be advanced in other ways.

Unable to rein in the unruly Turko-Mongol nobles, the Timurids rulers instead turned the lands which they administered directly. The areas around religious shrines were developed and patronized to gain a steady flow of income from traveling pilgrims as well as provide legitimacy to the ruler. Canals were cleared and irrigation lines dug, thus allowing for agriculture to develop and pilgrims to be fed. Nonetheless, the development was done in part through use of charitable endowments which were often untaxable. That prevented those developments from making up for the state’s weakness.

In the end, the Timurids were swept away by the Uzbeks and Safavids in the beginning of the 16th century. Their dynasty had grown soft with urban life, its members incapable of organizing and leading armies as their steppe barbarian ancestors had. Their weak state similarly prevented the raising of professional armies which could have also enabled them to endure.

The Timurids were not the only ones who had been faced with the dilemma of civilization and barbarism. Should a conquering dynasty allow its nobility broad autonomy and great wealth in order to secure their loyalty, even though it requires them to practice collaborative government and weaken state finances? Or should it solidify state authority, secure its finances, and rule through a bureaucracy that cause its natural military base of support to erode away? The nobility reappear time and time again in history for a reason after all. A ruler needs strong friends who can bring him skilled fighting men in his hour of need.

Richard Hovannisian and his co-authors implicitly argue that the former position is more robust historically. The Armenians descend in part from a group of steppe refugees who fled defeat at the hands of the Indo-Iranians in the 26th or 25th century BC to their current home on the other, southern side of the Caucasus Mountains. The mountainous and hilly geography of the South Caucasus allowed for the survival of numerous groups both past and present, and also impeded political centralization.

The Armenians in their early historical period (late 1st millennium BC and early 1st millennium AD) were dominated by their naxarar nobility even though they had a nominal king. The naxarars had large families, and worked hard to keep their lands within their family. As such, they rarely went extinct. They kept their own armies and could even sponsor their own choice of religion until the Zoroastrians were finally defeated and forced out into Persia.

During the great and terrible struggles between the Romans and the Persians in the 1st millennium AD, Armenia suffered immensely. Her lands were devastated repeatedly, her nobles and people drawn away to the safer empires, and Greek and Persian influences threatened to culturally absorb the Armenians. Nonetheless, Armenia endured due to her decentralized system. A naxarar might become a Greek or a Persian, he and his family might be wiped out, but other naxarars would survive – and from them Armenia would regenerate. Defeats could be endured.

It was centralization that ended up causing unprecedented devastation of Armenia. The rise of the Macedonian dynasty (867-1056 AD) in the Byzantine Empire revived the previously moribund empire’s fortunes, and led to renewed territorial expansion. Over the course of the 10th and 11th centuries, the Byzantines used their superior military strength and wealth to gradually gobble up the Armenian principalities. When they remained theoretically independent or autonomous under the Byzantines the nobility were still able to raise local militias to defend Armenia against Turk invaders from the east.

The Byzantines replaced the old naxarar administration with their centralized, bureaucratic form of administration after they formally annexed most of Armenia in the 11th century. Nobles and clergy were drawn by or relocated to the west by the Byzantines, far from the communities which they had guided for so long. The local Armenian militias were disbanded. As a result, the many powers in Armenia were replaced by one – and that one power was broken forever in 1071 at a place called Manzikert. Some Armenians would hold out in the mountains, but by and by large they would be swept away by the Turk nomads.

Armenia’s decentralized system of naxarars had endured Huns, Avars, Persians, Romans, and Arabs. Its centralization under the Byzantines didn’t allow it to endure even one invasion from the Turks.

The Timurids fell because they lost their warlike steppe barbarian attitudes while failing to build a strong agricultural state. The Armenians were overrun because the centralized empire they became a part of led to the atrophy of their political structure and society. Spanish America fell because the state which had once been a valuable mediator between its faraway subjects transformed into an alienating bureaucratic state.

The conquistadors and their successors initially lived and ruled in the Americas with a great deal of autonomy. Conquistadors were granted encomiendas by the crown, essentially areas where they ruled over the locals at their (sometimes cruel, sometimes kind) whim. They were only restricted by the interference of the Catholic Church and the audiencias – widely-respected courts which were heavily influenced by the local criollos (people of mostly Spanish-descent in the Americas).

As time went on, the Spanish government gradually centralized its authority. The abuses of the encomiendas were too widely known to be ignored, so the system was phased out. Nonetheless, poor governance in the 17th century led to a de facto policy that was equivalent of Colonial America’s salutary neglect, benefitting the criollos who could rule largely unemcumbered. That changed with the installation of the Bourbon dynasty on the throne of Spain.

Descended from the kings from France, the Bourbons brought French absolutism with them to Spain. Their reforms in the second half of the 18th century aimed at improving administration, increasing tax revenues, and financing defenses. They succeeded at all three, but in doing so undermined the stability of their colonial empire.

The previous system of Spanish colonial government involved corregidors and audiencias who were in theory supposed to be impartial representatives of the king, but in practice were highly partial and corrupt locals. The Bourbon reforms introduced a more centralized colonial administration of intendencias. Each intendencia was the size of several corregimientos, and extended royal authority much closer to the subjects.

Intendants as well as audiencia judges were chosen on the basis of their European, rather than criollo background in order to restore impartiality and reduce corruption. That was a highly effective move, increasing colonial revenues by about a third. The corregidors were incorrigibly enmeshed in local politics and corruption, whereas the intendants acted relatively impartially.

The impartiality alienated the criollos, whose opportunities for corruption at the public expense were reduced. Their avenues for promotion in the colonial bureaucracy were cut as well. The newly enforced taxes, while low, still left a bitter taste in their mouth. One sign of that was in the noticeable decrease in the number of children in Spain’s American colonies named after the local viceroy. In the end, a number of criollos took advantage of the chaos in Spain following Napoleon’s invasion to declare independence.

It could be useful to have barbarians in the service of a state, bound by custom and balance rather than bureaucracy. The invisible ties which bind them with their ruler may not be lucrative, but they were often necessary for the ability of a nation to endure serious shocks. How true that is today remains unknown.