Reznikov, a bald, bespectacled lawyer, said Ukraine’s military commanders were the ones making those decisions. But he noted that Ukraine’s armored vehicles were being destroyed by Russian helicopters, drones and artillery with every attempt to advance. Without air support, he said, the only option was to use artillery to shell Russian lines, dismount from the targeted vehicles and proceed on foot.

“We can’t maneuver because of the land-mine density and tank ambushes,” Reznikov said, according to an official who was present.

The meeting in Brussels, less than two weeks into the campaign, illustrates how a counteroffensive born in optimism has failed to deliver its expected punch, generating friction and second-guessing between Washington and Kyiv and raising deeper questions about Ukraine’s ability to retake decisive amounts of territory.

As winter approaches, and the front lines freeze into place, Ukraine’s most senior military officials acknowledge that the war has reached a stalemate.

This examination of the lead-up to Ukraine’s counteroffensive is based on interviews with more than 30 senior officials from Ukraine, the United States and European nations. It provides new insights and previously unreported details about America’s deep involvement in the military planning behind the counteroffensive and the factors that contributed to its disappointments. The second part of this two-part account examines how the battle unfolded on the ground over the summer and fall, and the widening fissures between Washington and Kyiv. Some of the officials spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive deliberations.

Key elements that shaped the counteroffensive and the initial outcome include:

● Ukrainian, U.S. and British military officers held eight major tabletop war games to build a campaign plan. But Washington miscalculated the extent to which Ukraine’s forces could be transformed into a Western-style fighting force in a short period — especially without giving Kyiv air power integral to modern militaries.

● U.S. and Ukrainian officials sharply disagreed at times over strategy, tactics and timing. The Pentagon wanted the assault to begin in mid-April to prevent Russia from continuing to strengthen its lines. The Ukrainians hesitated, insisting they weren’t ready without additional weapons and training.

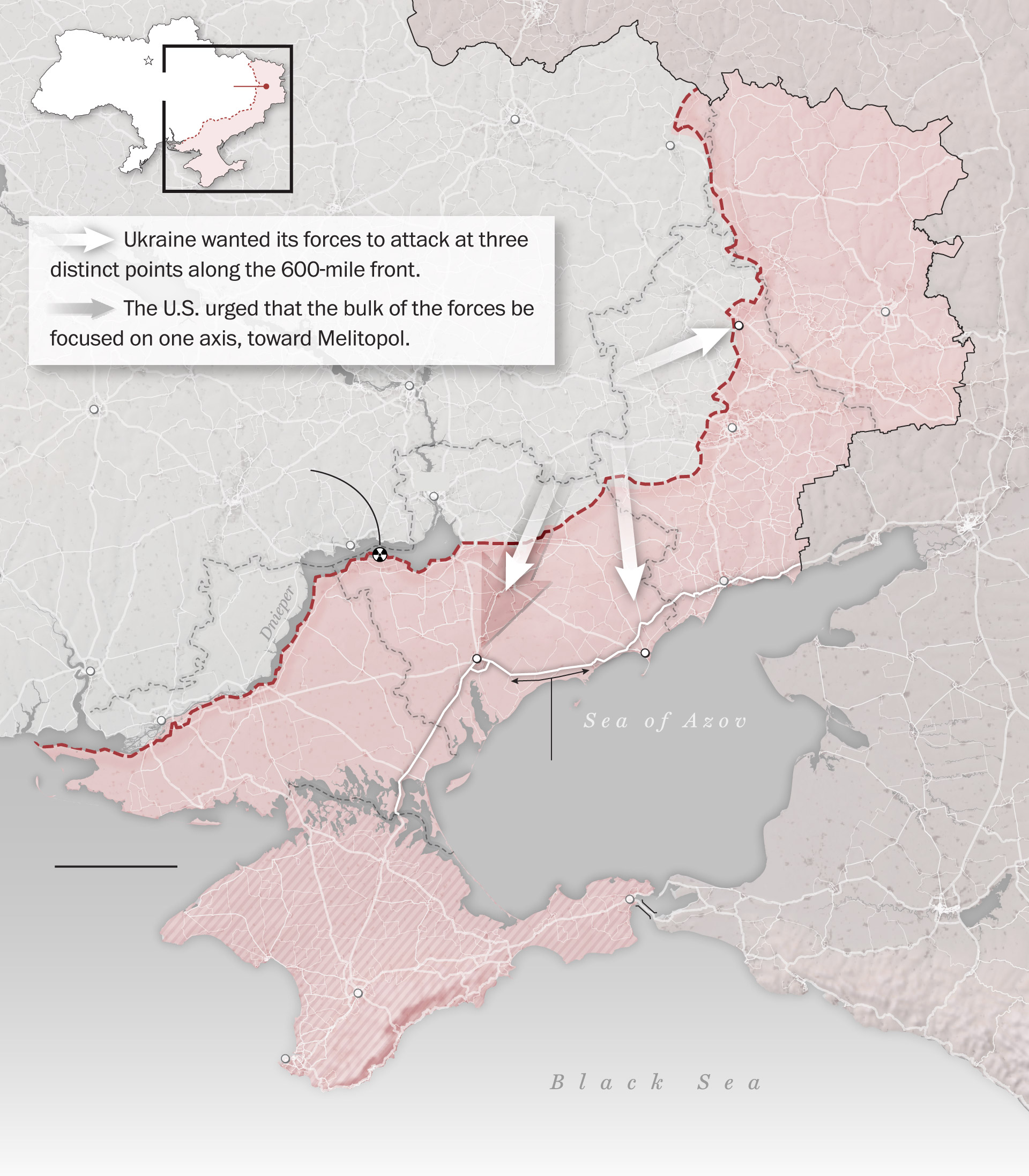

● U.S. military officials were confident that a mechanized frontal attack on Russian lines was feasible with the troops and weapons that Ukraine had. The simulations concluded that Kyiv’s forces, in the best case, could reach the Sea of Azov and cut off Russian troops in the south in 60 to 90 days.

● The United States advocated a focused assault along that southern axis, but Ukraine’s leadership believed its forces had to attack at three distinct points along the 600-mile front, southward toward both Melitopol and Berdyansk on the Sea of Azov and east toward the embattled city of Bakhmut.

The U.S. urged that the bulk of

the forces be focused on one axis, toward Melitopol.

Ukraine wanted its forces to attack

at three distinct points along the 600-mile front.

Nuclear power plant

at Enerhodar

Since the invasion, Russia controls this road,

which creates a “land bridge” to Crimea.

A goal of the Ukrainian counteroffensive

is to sever this connection.

Illegally annexed

by Russia

in 2014

Crimean Bridge

(Opened in 2018)

Sources: Institute for the Study of War, AEI’s Critical Threats Project

Ukraine wanted its forces to attack at three

distinct points along the 600-mile front.

The U.S. urged that the bulk of the forces be

focused on one axis, toward Melitopol.

Russian control

of this road creates a

“land bridge” to Crimea.

Illegally annexed

by Russia

in 2014

Crimean

Bridge

(Opened

in 2018)

Sources: Institute for the Study of War, AEI’s Critical Threats Project

Ukraine wanted its forces to attack

at three distinct points along

the 600-mile front.

The U.S. urged that the bulk of

the forces be focused on one axis,

toward Melitopol.

Illegally annexed

by Russia

in 2014

Crimean

Bridge

(Opened

in 2018)

Sources: Institute for the Study of War

Nuclear power plant

at Enerhodar

Since the invasion, Russia controls this road,

which creates a “land bridge” to Crimea.

A goal of the Ukrainian counteroffensive

is to sever this connection.

Illegally annexed

by Russia

in 2014

Crimean Bridge

(Opened in 2018)

Sources: Institute for the Study of War, AEI’s Critical Threats Project

● The U.S. intelligence community had a more downbeat view than the U.S. military, assessing that the offensive had only a 50-50 chance of success given the stout, multilayered defenses Russia had built up over the winter and spring.

● Many in Ukraine and the West underestimated Russia’s ability to rebound from battlefield disasters and exploit its perennial strengths: manpower, mines and a willingness to sacrifice lives on a scale that few other countries can countenance.

● As the expected launch of the offensive approached, Ukrainian military officials feared they would suffer catastrophic losses — while American officials believed the toll would ultimately be higher without a decisive assault.

The year began with Western resolve at its peak, Ukrainian forces highly confident and President Volodymyr Zelensky predicting a decisive victory. But now, there is uncertainty on all fronts. Morale in Ukraine is waning. International attention has been diverted to the Middle East. Even among Ukraine’s supporters, there is growing political reluctance to contribute more to a precarious cause. At almost every point along the front, expectations and results have diverged as Ukraine has shifted to a slow-moving dismounted slog that has retaken only slivers of territory.

“We wanted faster results,” Zelensky said in an interview with the Associated Press last week. “From that perspective, unfortunately, we did not achieve the desired results. And this is a fact.”

Together, all these factors make victory for Ukraine far less likely than years of war and destruction.

The campaign’s inconclusive and discouraging early months pose sobering questions for Kyiv’s Western backers about the future, as Zelensky — supported by an overwhelming majority of Ukrainians — vows to fight until Ukraine restores the borders established in its 1991 independence from the Soviet Union.

“That’s going to take years and a lot of blood,” a British security official said, if it’s even possible. “Is Ukraine up for that? What are the manpower implications? The economic implications? Implications for Western support?”

The year now stands to end with Russian President Vladimir Putin more certain than ever that he can wait out a fickle West and fully absorb the Ukrainian territory already seized by his troops.

Gaming out the battle plan

In a conference call in the late fall of 2022, after Kyiv had won back territory in the north and south, Austin spoke with Gen. Valery Zaluzhny, Ukraine’s top military commander, and asked him what he would need for a spring offensive. Zaluzhny responded that he required 1,000 armored vehicles and nine new brigades, trained in Germany and ready for battle.

“I took a big gulp,” Austin said later, according to an official with knowledge of the call. “That’s near-impossible,” he told colleagues.

In the first months of 2023, military officials from Britain, Ukraine and the United States concluded a series of war games at a U.S. Army base in Wiesbaden, Germany, where Ukrainian officers were embedded with a newly established command responsible for supporting Kyiv’s fight.

The sequence of eight high-level tabletop exercises formed the backbone for the U.S.-enabled effort to hone a viable, detailed campaign plan, and to determine what Western nations would need to provide to give it the means to succeed.

“We brought all the allies and partners together and really squeezed them hard to get additional mechanized vehicles,” a senior U.S. defense official said.

During the simulations, each of which lasted several days, participants were designated to play the part either of Russian forces — whose capabilities and behavior were informed by Ukrainian and allied intelligence — or Ukrainian troops and commanders, whose performance was bound by the reality that they would be facing serious constraints in manpower and ammunition.

The planners ran the exercises using specialized war-gaming software and Excel spreadsheets — and, sometimes, simply by moving pieces around on a map. The simulations included smaller component exercises that each focused on a particular element of the fight — offensive operations or logistics. The conclusions were then fed back into the evolving campaign plan.

Top officials including Gen. Mark A. Milley, then chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Col. Gen. Oleksandr Syrsky, commander of Ukrainian ground forces, attended several of the simulations and were briefed on the results.

During one visit to Wiesbaden, Milley spoke with Ukrainian special operations troops — who were working with American Green Berets — in the hope of inspiring them ahead of operations in enemy-controlled areas.

“There should be no Russian who goes to sleep without wondering if they’re going to get their throat slit in the middle of the night,” Milley said, according to an official with knowledge of the event. “You gotta get back there, and create a campaign behind the lines.”

Ukrainian officials hoped the offensive could re-create the success of the fall of 2022, when they recovered parts of the Kharkiv region in the northeast and the city of Kherson in the south in a campaign that surprised even Ukraine’s biggest backers. Again, their focus would be in more than one place.

But Western officials said the war games affirmed their assessment that Ukraine would be best served by concentrating its forces on a single strategic objective — a massed attack through Russian-held areas to the Sea of Azov, severing the Kremlin’s land route from Russia to Crimea, a critical supply line.

The rehearsals gave the United States the opportunity to say at several points to the Ukrainians, “I know you really, really, really want to do this, but it’s not going to work,” one former U.S. official said.

At the end of the day, though, it would be Zelensky, Zaluzhny and other Ukrainian leaders who would make the decision, the former official noted.

Officials tried to assign probabilities to different scenarios, including a Russian capitulation — deemed a “really low likelihood” — or a major Ukrainian setback that would create an opening for a major Russian counterattack — also a slim probability.

“Then what you’ve got is the reality in the middle, with degrees of success,” a British official said.

The most optimistic scenario for cutting the land bridge was 60 to 90 days. The exercises also predicted a difficult and bloody fight, with losses of soldiers and equipment as high as 30 to 40 percent, according to U.S. officials.

American military officers had seen casualties come in far lower than estimated in the major battles of Iraq and Afghanistan. They considered the estimates a starting point for planning medical care and battlefield evacuation so that losses never reached the projected levels.

The numbers “can be sobering,” the senior U.S. defense official said. “But they never are as high as predicted, because we know we have to do things to make sure we don’t.”

U.S. officials also believed that more Ukrainian troops would ultimately be killed if Kyiv failed to mount a decisive assault and the conflict became a drawn-out war of attrition.

But they acknowledged the delicacy of suggesting a strategy that would entail significant losses, no matter the final figure.

“It was easy for us to tell them in a tabletop exercise, ‘Okay, you’ve just got to focus on one place and push really hard,’” a senior U.S. official said. “They were going to lose a lot of people and they were going to lose a lot of the equipment.”

Those choices, the senior official said, become “much harder on the battlefield.”

On that, a senior Ukrainian military official agreed. War-gaming “doesn’t work,” the official said in retrospect, in part because of the new technology that was transforming the battlefield. Ukrainian soldiers were fighting a war unlike anything NATO forces had experienced: a large conventional conflict, with World World I-style trenches overlaid by omnipresent drones and other futuristic tools — and without the air superiority the U.S. military has had in every modern conflict it has fought.

“All these methods … you can take them neatly and throw them away, you know?” the senior Ukrainian said of the war-game scenarios. “And throw them away because it doesn’t work like that now.”

Disagreements about deployments

The Americans had long questioned the wisdom of Kyiv’s decision to keep forces around the besieged eastern city of Bakhmut.

Ukrainians saw it differently. “Bakhmut holds” had become shorthand for pride in their troops’ fierce resistance against a bigger enemy. For months, Russian and Ukrainian artillery had pulverized the city. Soldiers killed and wounded one another by the thousands to make gains measured sometimes by city blocks.

The city finally fell to Russia in May.

Zelensky, backed by his top commander, stood firm about the need to retain a major presence around Bakhmut and strike Russian forces there as part of the counteroffensive. To that end, Zaluzhny maintained more forces near Bakhmut than he did in the south, including the country’s most experienced units, U.S. officials observed with frustration.

Ukrainian officials argued that they needed to sustain a robust fight in the Bakhmut area because otherwise Russia would try to reoccupy parts of the Kharkiv region and advance in Donetsk — a key objective for Putin, who wants to seize that whole region.

“We told [the Americans], ‘If you assumed the seats of our generals, you’d see that if we don’t make Bakhmut a point of contention, [the Russians] would,’” one senior Ukrainian official said. “We can’t let that happen.”

In addition, Zaluzhny envisioned making the formidable length of the 600-mile front a problem for Russia, according to the senior British official. The Ukrainian general wanted to stretch Russia’s much larger occupying force — unfamiliar with the terrain and already facing challenges with morale and logistics — to dilute its fighting power.

Western officials saw problems with that approach, which would also diminish the firepower of Ukraine’s military at any single point of attack. Western military doctrine dictated a concentrated push toward a single objective.

The Americans yielded, however.

“They know the terrain. They know the Russians,” said a senior U.S. official. “It’s not our war. And we had to kind of sit back into that.”

On Feb. 3, Jake Sullivan, President Biden’s national security adviser, called together the administration’s top national security officials to review the counteroffensive plan.

The White House’s subterranean Situation Room was being renovated, so the top echelons of the State, Defense and Treasury departments, along with the CIA, gathered in a secure conference room in the adjacent Eisenhower Executive Office Building.

Most were already familiar with Ukraine’s three-pronged approach. The goal was for Biden’s senior advisers to voice their approval or reservations to one another and try to reach consensus on their joint advice to the president.

The questions posed by Sullivan were simple, said a person who attended. First, could Washington and its partners successfully prepare Ukraine to break through Russia’s heavily fortified defenses?

And then, even if the Ukrainians were prepared, “could they actually do it?”

Milley, with his ever-ready green maps of Ukraine, displayed the potential axes of attack and the deployment of Ukrainian and Russian forces. He and Austin explained their conclusion that “Ukraine, to be successful, needed to fight a different way,” one senior administration official closely involved in the planning recalled.

Ukraine’s military, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, had become a defensive force. Since 2014 it had focused on a grinding but low-level fight against Russian-backed forces in the eastern Donbas region. To orchestrate a large-scale advance would require a significant shift in its force structure and tactics.

The planning called for wider and better Western training, which up to that point had focused on teaching small groups and individuals to use Western-provided weapons. Thousands of troops would be instructed in Germany in large unit formations and U.S.-style battlefield maneuvers, whose principles dated to World War II. For American troops, training in what was known as “combined arms” operations often lasted more than a year. The Ukraine plan proposed condensing that into a few months.

Instead of firing artillery, then “inching forward” and firing some more, the Ukrainians would be “fighting and shooting at the same time,” with newly trained brigades moving forward with armored vehicles and artillery support “in a kind of symphonic way,” the senior administration official said.

The Biden administration announced in early January that it would send Bradley Fighting Vehicles; Britain agreed to transfer 14 Challenger tanks. Later that month, after a grudging U.S. announcement that it would provide top-line Abrams M1 tanks by the fall, Germany and other NATO nations pledged hundreds of German-made Leopard tanks in time for the counteroffensive.

A far bigger problem was the supply of 155mm shells, which would enable Ukraine to compete with Russia’s vast artillery arsenal. The Pentagon calculated that Kyiv needed 90,000 or more a month. While U.S. production was increasing, it was barely more than a tenth of that.

“It was just math,” the former senior official said. “At a certain point, we just wouldn’t be able to provide them.”

Sullivan laid out options. South Korea had massive quantities of the U.S.-provided munitions, but its laws prohibited sending weapons to war zones. The Pentagon calculated that about 330,000 155mm shells could be transferred by air and sea within 41 days if Seoul could be persuaded.

Senior administration officials had been speaking with counterparts in Seoul, who were receptive as long as the provision was indirect. The shells began to flow at the beginning of the year, eventually making South Korea a larger supplier of artillery ammunition for Ukraine than all European nations combined.

The more immediate alternative would entail tapping the U.S. military’s arsenal of 155mm shells that, unlike the South Korean variant, were packed with cluster munitions. The Pentagon had thousands of them, gathering dust for decades. But Secretary of State Antony Blinken balked.

Inside the warhead of those cluster weapons, known officially as Dual-Purpose Improved Conventional Munitions, or DPICMs, were dozens of bomblets that would scatter across a wide area. Some would inevitably fail to explode, posing a long-term danger to civilians, and 120 countries — including most U.S. allies but not Ukraine or Russia — had signed a treaty banning them. Sending them would cost the United States some capital on the war’s moral high ground.

In the face of Blinken’s strong objections, Sullivan tabled consideration of DPICMs. They would not be referred to Biden for approval, at least for now.

With the group agreeing that the United States and allies could provide what they believed were the supplies and training Ukraine needed, Sullivan faced the second part of the equation: Could Ukraine do it?

Zelensky, on the war’s first anniversary in February, had boasted that 2023 would be a “year of victory.” His intelligence chief had decreed that Ukrainians would soon be vacationing in Crimea, the peninsula that Russia had illegally annexed in 2014. But some in the U.S. government were less than confident.

U.S. intelligence officials, skeptical of the Pentagon’s enthusiasm, assessed the likelihood of success at no better than 50-50. The estimate frustrated their Defense Department counterparts, especially those at U.S. European Command, who recalled the spies’ erroneous prediction in the days before the 2022 invasion that Kyiv would fall to the Russians within days.

Some defense officials observed caustically that optimism was not in intelligence officials’ DNA — they were the “Eeyores” of government, the former senior official said, and it was always safer to bet on failure.

“Part of it was just the fact of the sheer weight of the Russian military,” CIA Director William J. Burns later reflected in an interview. “For all their incompetence in the first year of the war, they had managed to launch a shambolic partial mobilization to fill a lot of the gaps in the front. In Zaporizhzhia” — the key line of the counteroffensive if the land bridge was to be severed — “we could see them building really quite formidable fixed defenses, hard to penetrate, really costly, really bloody for the Ukrainians.”

Perhaps more than any other senior official, Burns, a former ambassador to Russia, had traveled multiple times to Kyiv over the previous year, sometimes in secret, to meet with his Ukrainian counterparts, as well as with Zelensky and his senior military officials. He appreciated the Ukrainians’ most potent weapon — their will to fight an existential threat.

“Your heart is in it,” Burns said of his hopes for helping Ukraine succeed. “But … our broader intelligence assessment was that this was going to be a really tough slog.”

Two weeks after Sullivan and others briefed the president, a top-secret, updated intelligence report assessed that the challenges of massing troops, ammunition and equipment meant that Ukraine would probably fall “well short” of its counteroffensive goals.

The West had so far declined to grant Ukraine’s request for fighter jets and the Army Tactical Missile System, or ATACMS, which could reach targets farther behind Russian lines, and which the Ukrainians felt they needed to strike key Russian command and supply sites.

“You are not going to go from an emerging, post-Soviet legacy military to the U.S. Army of 2023 overnight,” a senior Western intelligence official said. “It is foolish for some to expect that you can give them things and it changes the way they fight.”

U.S. military officials did not dispute that it would be a bloody struggle. By early 2023, they knew that as many as 130,000 Ukrainian troops had been injured or killed in the war, including many of the country’s best soldiers. Some Ukrainian commanders were already expressing doubts about the coming campaign, citing the numbers of troops who lacked battlefield experience.

Yet the Pentagon had also worked closely with Ukrainian forces. Officials had watched them fight courageously and had overseen the effort to provide them with large amounts of sophisticated arms. U.S. military officials argued that the intelligence estimates failed to account for the firepower of the newly arriving weaponry, as well as the Ukrainians’ will to win.

“The plan that they executed was entirely feasible with the force that they had, on the timeline that we planned out,” a senior U.S. military official said.

Austin knew that additional time for training on new tactics and equipment would be beneficial but that Ukraine didn’t have that luxury.

“In a perfect world, you get a choice. You keep saying, ‘I want to take six more months to train up and feel comfortable about this,’” he said in an interview. “My take is that they didn’t have a choice. They were in a fight for their lives.”

By March, Russia was already many months into preparing its defenses, building miles upon miles of barriers, trenches and other obstacles across the front in anticipation of the Ukrainian push.

After stinging defeats in the Kharkiv region and Kherson in the fall of 2022, Russia seemed to pivot. Putin appointed Gen. Sergei Surovikin — known as “General Armageddon” for his merciless tactics in Syria — to lead Russia’s fight in Ukraine, focusing on digging in rather than taking more territory.

In the months after the 2022 invasion, Russian trenches were basic — flood-prone, straight-line pits nicknamed “corpse lines,” according to Ruslan Leviev, an analyst and co-founder of the Conflict Intelligence Team, which has been tracking Russian military activity in Ukraine since 2014.

But Russia adapted as the war wore on, digging drier, zigzagging trenches that better protected soldiers from shelling. As the trenches eventually grew more sophisticated, they opened up into forests to offer better means for defenders to fall back, Leviev said. The Russians built tunnels between positions to counter Ukraine’s extensive use of drones, he added.

The trenches were part of multilayered defenses that included dense minefields, concrete pyramids known as dragon’s teeth, and antitank ditches. If minefields were disabled, Russian forces had rocket-borne systems to reseed them.

Unlike Russia’s offensive efforts early in the war, these defenses followed textbook Soviet standards. “This is one case where they have implemented their doctrine,” a senior Western intelligence official said.

Konstantin Yefremov, a former officer with Russia’s 42nd motorized rifle division who was stationed in Zaporizhzhia in 2022, recalled that Russia had the equipment and grunt power necessary to build a solid wall against attack.

“Putin’s army is experiencing shortages of various arms, but can literally swim in mines,” Yefremov said in an interview after fleeing to the West. “They have millions of them, both antitank and antipersonnel mines.”

The poverty, desperation and fear of the tens of thousands of conscripted Russian soldiers made them an ideal workforce. “All you need is slave power,” he said. “And even more so, Russian rank-and-file soldiers know they are [building trenches and other defenses] for themselves, to save their skin.”

In addition, in a tactic used in both World War I and II, Surovikin would deploy blocking units behind the Russian troops to prevent them from retreating, sometimes under pain of death.

Their options were “either to die from our units or from their own,” said Ukrainian police Col. Oleksandr Netrebko, the commander of a newly formed police brigade fighting near Bakhmut.

Yet, while Russia had far more troops, a deeper military arsenal and what one U.S. official said was “just a willingness to endure really dramatic losses,” U.S. officials knew it also had serious vulnerabilities.

By early 2023, some 200,000 Russian soldiers had been killed or wounded, U.S. intelligence agencies estimated, including scores of highly trained commandos. Replacement troops who were rushed into Ukraine lacked experience. Turnover of field leaders had hurt command and control. Equipment losses were equally staggering: more than 2,000 tanks, some 4,000 armored fighting vehicles and at least 75 aircraft, according to a Pentagon document leaked on the Discord chat platform in the spring.

The assessment was that the Russian force was insufficient to protect every line of conflict. But unless Ukraine got underway quickly, the Kremlin could make up its deficits inside of a year, or less if it got more outside help from friendly nations such as Iran and North Korea.

It was imperative, U.S. officials argued, for Ukraine to launch.

More troops, more weapons

In late April, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg made an unannounced trip to see Zelensky in Kyiv.

Stoltenberg, a former Norwegian prime minister, was in town to discuss preparations for the NATO summit in July, including Kyiv’s push to join the alliance.

But over a working lunch with a handful of ministers and aides, talk turned to preparation for the counteroffensive — how things were going and what was left to be done.

Stoltenberg — due the next day in Germany for a meeting of the Ukraine Defense Contact Group, a consortium of roughly 50 countries providing weaponry and other support to Kyiv — asked about efforts to equip and train Ukrainian brigades by the end of April, according to two people familiar with the talks.

Zelensky reported that the Ukrainian military expected the brigades to be at 80 or 85 percent by the end of the month, the people said. That seemed at odds with American expectations that Ukraine should already be ready to launch.

The Ukrainian leader also stressed that his troops had to hold the east to keep Russia from shifting forces to block Kyiv’s southern counteroffensive. To defend the east while also pushing south, he said, Ukraine needed more brigades, the two people recalled.

Ukrainian officials also continued to make the case that an expanded arsenal was central to their ability to succeed. It wasn’t until May, on the eve of the fight, that Britain announced it would provide longer-range Storm Shadow missiles. But another core refrain from Ukraine was that they were being asked to fight in a way no NATO nation would ever contemplate — without effective power in the air.

As one former senior Ukrainian official pointed out, his country’s aging MiG-29 fighter jets could detect targets within a 40-mile radius and fire at a range of 20 miles. Russia’s Su-35s, meanwhile, could identify targets more than 90 miles away and shoot them down as far away as 75 miles.

“Imagine a MiG and a Su-35 in the sky. We don’t see them while they see us. We can’t reach them while they can reach us,” the official said. “That’s why we fought so hard for F-16s.”

American officials pointed out that even a few of the $60 million aircraft would eat up funds that could go much further in buying vehicles, air defenses or ammunition. Moreover, they said, the jets wouldn’t provide the air superiority the Ukrainians craved.

“If you could train a bunch of F-16 pilots in three months, they would have got shot down on day one, because the Russian air defenses in Ukraine are very robust and very capable,” a senior defense official said.

Biden finally yielded in May and granted the required permission for European nations to donate their U.S.-made F-16s to Ukraine. But pilot training and delivery of the jets would take a year or more, far too long to make a difference in the coming fight.

By May, concern was growing within the Biden administration and among allied backers. According to the planning, Ukraine should have already launched its operations. As far as the U.S. military was concerned, the window of opportunity was shrinking fast. Intelligence over the winter had shown that Russian defenses were relatively weak and largely unmanned, and that morale was low among Russian troops after their losses in Kharkiv and Kherson. U.S. intelligence assessed that senior Russian officers felt the prospects were bleak.

But that assessment was changing quickly. The goal had been to strike before Moscow was ready, and the U.S. military had been trying since mid-April to get the Ukrainians moving. “We were given dates. We were given many dates,” a senior U.S. government official said. “We had April this, May that, you know, June. It just kept getting delayed.”

Meanwhile, enemy defenses were thickening. U.S. military officials were dismayed to see Russian forces use those weeks in April and May to seed significant amounts of additional mines, a development the officials believed ended up making Ukrainian troops’ advance substantially harder.

Washington was also getting worried that the Ukrainians were burning up too many artillery shells, primarily around Bakhmut, that were needed for the counteroffensive.

As May ground on, it seemed to the Americans that Kyiv, gung-ho during the war games and the training, had abruptly slowed down — that there was “some type of switch in psychology” where they got to the brink “and then all of a sudden they thought, ‘Well, let’s triple-check, make sure we’re comfortable,’” said one administration official who was part of the planning. “But they were telling us for almost a month … ‘We’re about to go. We’re about to go.’”

Some senior American officials believed there wasn’t conclusive proof that the delay had altered Ukraine’s chances for success. Others saw clear indications that the Kremlin had successfully exploited the interim along what it believed would be Kyiv’s lines of assault.

In Ukraine, a different kind of frustration was building. “When we had a calculated timeline, yes, the plan was to start the operation in May,” said a former senior Ukrainian official who was deeply involved in the effort. “However, many things happened.”

Promised equipment was delivered late or arrived unfit for combat, the Ukrainians said. “A lot of weapons that are coming in now, they were relevant last year,” the senior Ukrainian military official said, not for the high-tech battles ahead. Crucially, he said, they had received only 15 percent of items — like the Mine Clearing Line Charge launchers (MCLCs) — needed to execute their plan to remotely cut passages through the minefields.

And yet, the senior Ukrainian military official recalled, the Americans were nagging about a delayed start and still complaining about how many troops Ukraine was devoting to Bakhmut.

U.S. officials vehemently denied that the Ukrainians did not get all the weaponry they were promised. Ukraine’s wish list may have been far bigger, the Americans acknowledged, but by the time the offensive began, they had received nearly two dozen MCLCs, more than 40 mine rollers and excavators, 1,000 Bangalore torpedoes, and more than 80,000 smoke grenades. Zaluzhny had requested 1,000 armored vehicles; the Pentagon ultimately delivered 1,500.

“They got everything they were promised, on time,” one senior U.S. official said. In some cases, the officials said, Ukraine failed to deploy equipment critical to the offensive, holding it in reserve or allocating it to units that weren’t part of the assault.

Then there was the weather. The melting snow and heavy rains that turn parts of Ukraine into a soup of heavy mud each spring had come late and lasted longer than usual.

In the middle of 2022, when the thinking about a counteroffensive began, “no one knew the weather forecast,” the former senior Ukrainian official said.

That meant it was unclear when the flat plains and rich black soil of southeastern Ukraine, which could act as a glue grabbing hold of boots and tires, would dry out for summer. The Ukrainians understood the uncertainty because they, unlike the Americans, lived there.

As the preparations accelerated, Ukrainian officials’ concerns grew more acute, erupting at a meeting at Ramstein Air Base in Germany in April when Zaluzhny’s deputy, Mykhailo Zabrodskyi, made an emotional appeal for help.

“We’re sorry, but some of the vehicles we received are unfit for combat,” Zabrodskyi told Austin and his aides, according to a former senior Ukrainian official. He said the Bradleys and Leopards had broken or missing tracks. German Marder fighting vehicles lacked radio sets; they were nothing more than iron boxes with tracks — useless if they couldn’t communicate with their units, he said. Ukrainian officials said the units for the counteroffensive lacked sufficient de-mining and evacuation vehicles.

Austin looked at Gen. Christopher Cavoli, the top U.S. commander for Europe, and Lt. Gen. Antonio Aguto, head of the Security Assistance Group-Ukraine, both sitting next to him. They said they’d check.

The Pentagon concluded that Ukrainian forces were failing to properly handle and maintain all the equipment after it was received. Austin directed Aguto to work more intensively with his Ukrainian counterparts on maintenance.

“Even if you deliver 1,300 vehicles that are working fine, there’s going to be some that break between the time that you get them on the ground there and the time they enter combat,” a senior defense official said.

By June 1, the top echelons at U.S. European Command and the Pentagon were frustrated and felt like they were getting few answers. Maybe the Ukrainians were daunted by the potential casualties? Perhaps there were political disagreements within the Ukrainian leadership, or problems along the chain of command?

The counteroffensive finally lurched into motion in early June. Some Ukrainian units quickly notched small gains, recapturing Zaporizhzhia-region villages south of Velyka Novosilka, 80 miles from the Azov coast. But elsewhere, not even Western arms and training could fully shield Ukrainian forces from the punishing Russian firepower.

When troops from the 37th Reconnaissance Brigade attempted an advance, they, like units elsewhere, immediately felt the force of Russia’s tactics. From the first minutes of their assault, they were overwhelmed by mortar fire that pierced their French AMX-10 RC armored vehicles. Their own artillery fire didn’t materialize as expected. Soldiers crawled out of burning vehicles. In one unit, 30 of 50 soldiers were captured, wounded or killed. Ukraine’s equipment losses in the initial days included 20 Bradley Fighting Vehicles and six German-made Leopard tanks.

Those early encounters landed like a thunderbolt among the officers in Zaluzhny’s command center, searing a question in their minds: Was the strategy doomed?

Stalemate: Ukraine’s failed counteroffensive. This is part one of a two-part series. Read part two here.

Story editing by Peter Finn and David M. Herszenhorn. Project editing by Reem Akkad. Graphics by Laris Karklis. Graphics editing by Samuel Granados. Photo illustrations by Emily Sabens. Photo editing by Olivier Laurent. Copy editing by Martha Murdock.