By

The experience of diving varies from place to place, but the first thing you usually feel is the cooling sensation of jumping in the water. A lot of times you’re quite hot before you get in because you’re putting on a suit. Plus here in Florida, it’s warm anyway.

Then: Silence. You feel your heart beating. Your range of focus narrows as you’re pulling down the anchor line. Your eyes strain to make out what’s in the distance as you sink deeper and the ambient light dims.

You see the fish who come out to greet you; the first sign you’re close to the bottom. You squeeze your nose to clear your ears because of the increased pressure, like when you’re on a plane.

Once you reach the bottom, your heart races as you pick out recognizable features and put the puzzle pieces together in your mind. Your brain buzzes trying to make sense of it all.

A lot of people think about shipwrecks as a Hollywood movie; a vessel sitting at the bottom of the sea, intact, like a ghost ship. That’s just not the case unless it sank hours beforehand.

The HISTORY® Channel

Gravity works underwater. The forces of storms and surges and currents break wrecks apart. They sand over and get encrusted, and so are well camouflaged, and usually scattered across the ocean floor. It looks to most people like a big junk pile.

If visibility is poor, you’re often only seeing a small portion of a large ship. It requires a lot of mental visualization to make sense of the chaotic scene on the bottom. We’re gathering information to document the site and get data on the type of vessel and its age.

Thousands of Shipwrecks

This all started for me for me when I was a marine science student at the University of South Carolina back in 1990, my sophomore year. I took basic open water scuba diving training there.

I was fascinated with shipwrecks and maritime history, and it went hand in hand with a marine biology career. I pursued local dive sites that you could walk into, like rivers and lakes, and did some fossil diving. Quickly, I gravitated towards shipwreck diving when I could get out offshore.

My passion for diving launched from there. I lived in Charleston, South Carolina, where there’s a lot of maritime history related to the Civil War. Then I lived in Virginia Beach and up there it’s the mid-Atlantic, so you don’t have coral reefs or anything like that. It’s all wreck diving. That’s where underwater exploration really blossomed for me in the mid-nineties.

By 1998, I was living down in Florida. It’s very popular for scuba diving. I thought all the wrecks had been found and identified. But I was amazed to learn that wasn’t the case.

I was by myself at first, until I found a small band of other misfits like me who were interested in trying to search out mystery shipwrecks, and we started building up a track record of discoveries.

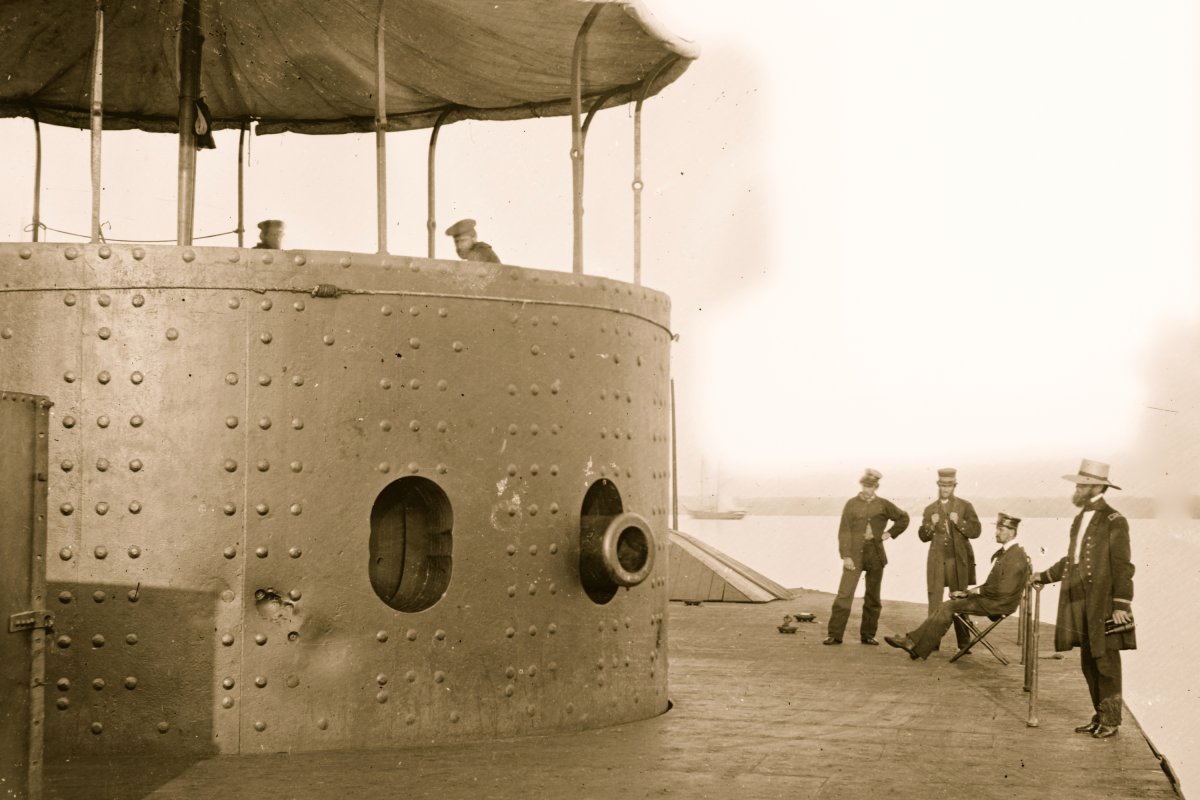

I branched out into a lot of international work and I was fortunate to dive historical shipwrecks, such as the USS Monitor of North Carolina, which is an ironclad ship that marked a turning point from wooden to modern warships.

I dived the SS Andrea Doria, an Italian ocean liner that sank in the North Atlantic in 1956; and the HMHS Britannic, which is a sister ship of the White Star Line’s RMS Titanic and sank in 1916 when it hit a German mine in the Aegean Sea. And I’ve done the RMS Lusitania, an ocean liner torpedoed off the Irish coast by a German U-boat in 1915.

I’ve dived thousands of shipwrecks, but there’s only a small handful you can name to non-divers that they’re familiar with, like the Lusitania and Monitor. People have heard of those through pop culture or as kids learning in school.

The HISTORY® Channel

I remember my first wreck dive when I was in college. It was a horrendous experience.

We went offshore at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, to dive a Civil War blockade runner. It was in the springtime and cold. The trip was long and rough amid the diesel fumes. I was sick as a dog, asking myself: “Why am I doing this? I could have slept in.”

But I stuck it out. Once I got the water and saw all that twisted metal and wooden remains of this Civil War-era steamer, I was hooked. Sometimes you wonder why we do the things we do. But that’s what it takes to forge new discoveries.

Curiosity is my main motivator. It’s the driving force of all explorers trying to learn more about our world. Everyone thinks the planet is getting smaller; that we’ve seen and done everything.

But three-quarters of our planet is covered by water. There are a lot of secrets to be found.

Having done this for so long now, 35 years, I’ve lost several friends. I knew someone who was onboard the Titan submersible that imploded. That was deep sea exploration, which is quite unlike what we do.

This year alone I’ve lost two very close friends from diving accidents. It’s a tragic reminder that you must be mentally and physically fit and not to take anything for granted—don’t get complacent.

There’s very little room for error. If something goes wrong, you must respond correctly. If you don’t, problems can multiply into a situation from which you are not able to extricate yourself. You will pay the price for it.

We know the cost of a screw up. It’s always on our mind.

Bermuda Triangle

The second series of our HISTORY Channel show “The Bermuda Triangle: Into Cursed Waters” is premiering on November 14, 2023. But the Bermuda Triangle wasn’t originally an area of interest to me as a scientist.

I don’t entertain the paranormal. I think everything has a rational explanation, but, for better or worse, the Bermuda Triangle captures people’s imaginations.

It garners a lot of attention for lost vessels and aircraft in this area, so it’s been a great vehicle for me to pursue these lost ships. And we have found several, such as the WWI-era SS Cotopaxi and the Costa Rican cargo ship Sandra, which disappeared in 1950.

When we find those ships, we can provide a rational explanation for their losses, and share that it’s not an abstract thing, this triangle with “mystical” properties. These are human stories. There are human lives lost when a ship founders in a storm or an aircraft disappears.

I use the lore of the Bermuda Triangle to get people’s attention and share these bits of history, and reveal that you don’t need to add the drama of a Bermuda Triangle, or a wormhole, or UFOs.

The stories that we share of storms, fire, human error, neglect of the vessel—all these lead to tragedies at sea. We pull back the curtain on these losses and prove that such things happen.

And they’re happening to this very day. Ships and aircraft are lost every year. The Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 is a great example of how we have not yet documented every inch of our planet. There are a lot of hiding places in the ocean.

The HISTORY® Channel

A totally unexpected discovery we made was a 20ft segment of the Space Shuttle Challenger back in the first season. We actually found that outside of the Bermuda Triangle when we were looking for another aircraft; the Martin PBM-5 Mariner associated with Flight 19.

We used NASA data from 1986 when the Challenger blew up and they had searched the whole area to recover all the matter from the orbiter and the solid rocket boosters. They came across some other stuff—some geology and shipping containers—and mentioned a couple of aircraft.

We were looking for this potential aircraft and trying to eliminate all possibilities when we stumbled across a piece of the Challenger. It was quite a shock. We realized what it was quickly and had it confirmed by a friend of mine who was a two-time shuttle astronaut. We were blown away.

I’ve been on dives for hundreds and hundreds of ships, some of them very historical, but it can be quite abstract for me if the events are from centuries before I was born. But I remember the Challenger.

I remember where I was, being a high school student and seeing it unfold live on TV. It really etched into my memory. I’ve carried that memory all these years. The serendipity of being part of that Challenger discovery was shocking and extremely moving.

There’s no question that has been the most surprising and probably the biggest discovery I’ve made.

History Comes Alive

People ask me what’s my favorite discovery and I always say: It’s the next dive.

Once we identify a ship and reveal the history, I feel the need to move on to the next project; the next unknown. There are millions of lost ships out there still waiting to be found. There is lifetimes upon lifetimes of work left to do.

I had a phenomenal dive a few years ago for the Britannic when we were doing a penetration of the wreck into the engine room. We found the manufacturer’s plaque; it was the first time it had been seen. We found unexpected documentation on this plaque that will be revealed, hopefully, soon.

Another special memory is from the USS Monitor and the ironclad turret down there. You see those iconic pictures after the Battle of Hampton Roads between the CSS Virginia and the Monitor, and there are dents in the side of the latter’s turret.

I was down there on the wreck. It’s upside down. I’ve seen the turret and those dents that I saw in a picture in history class when I was a young kid.

When history comes alive like that, it’s just remarkable. It’s not sterile anymore. It’s not just being dictated to you. You’re living it, and that is incredibly moving.

Buyenlarge/Getty Images

Most of the wrecks out there—and hopefully people will understand what I’m saying by this—are not historically significant. Some of them are quite significant, but these are really the 18-wheeler lorries of their day, carrying standard cargo.

A lot of times we recover artifacts because that’s one of the quickest ways to get proof positive of the ship’s name. You can get a patent date or number when you find the shipping line on a piece of China. These are all clues.

Also, we were personally funded for many dives. We did this all on our own dime and our own time. We don’t have grants like academic archaeologists who can work one shipwreck for years and years. We don’t have that luxury of time or funding.

So we try to we try to expedite the process by recovering artifacts. That is, I’m sure, a debate that archaeologists would love to jump on. But I’m also very conscious of when we dive something that is obviously, even to an amateur like me, historically significant.

We bring those to the attention of archaeologists and historians. I’ve done it numerous times throughout my career. We’ve documented quite a few ships.

One was the Queen of Nassau, which was originally built as the Canadian government ship HMCS Canada. It was a flagship of the Canadian Navy at one point; the second most historical ship in Canadian maritime history.

In our first dive, it was obvious that this was something unique and that led to the identification of it. A friend of mine, an archaeologist, did his thesis on it because it was that significant.

There are just so many discoveries to be made out there. A lot of times, shipwrecks have been found accidentally, whether it be by a fishing trawler’s net, laying a pipeline or fiber optic cable, building a wind farm, bathymetric surveys, geological research, and so on.

I’ve worked with a lot of fishermen and tapped into their knowledge base because the sea is their office. These guys know where every little bump on the bottom is, including ones they can’t identify.

I have quite a few lost ships that are works in progress right now.

I’m hesitant to name names because you might be hearing about them in a season three of “Into Cursed Waters”. There are potential claim jumpers or people looking for the same things. It can be competitive, as weird as that is for such a fringe thing.

So for now, I just have to hold some of that stuff close.

Michael C. Barnette is a marine biologist with NOAA, an accomplished diver, author, and photographer/videographer based in St. Petersburg, Florida. He is part of the team of investigators for “The Bermuda Triangle: Into Cursed Waters”. Season 2 is premiering on The HISTORY Channel on Tuesday, November 14, 2023.

All views expressed are the author’s own.

As told to Shane Croucher.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? Email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.