There are certain works—paintings, films, books, gardens—that have an effect on me that I can only describe by saying: in their presence, I remember that I am a human being. Shallow dry falls. In this series, I share works that have this effect on me, along with a short essay explaining what I see in them.

See also, part 1.

Christ tearing down the gates of hell, Unknown artist imitating Hieronymus Bosch, 1540-60

me

During the incendiary bombing of Dresden, a survivor claims that a building incinerated with phosphorus became so overheated that violent drafts blew in and people fleeing down the street were blown through windows and doors. This is almost certainly made up, but it captures something of the surreal intensity of the terror that Allied forces inflicted on the population of Dresden in February 1945.

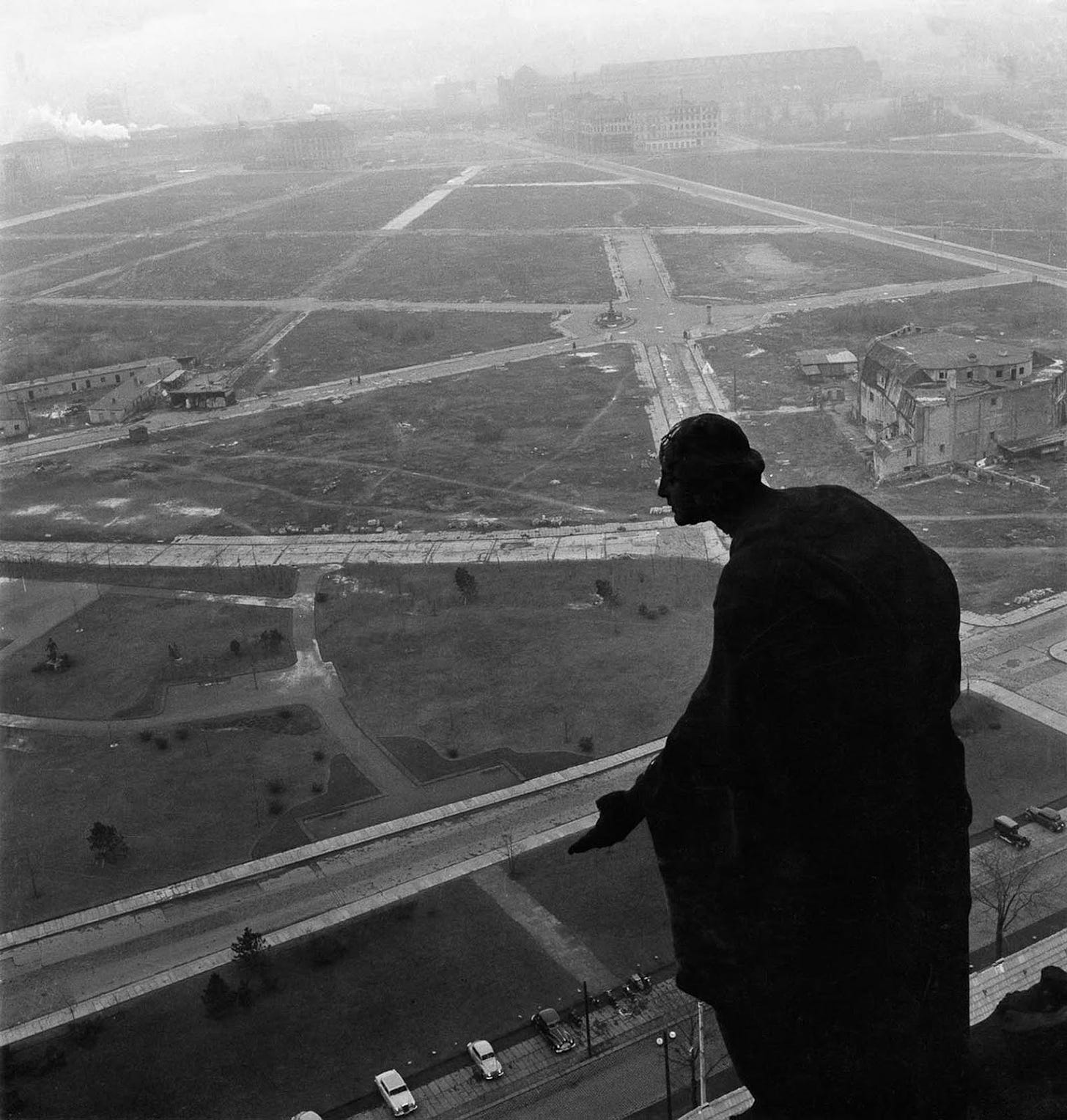

Seven months after the attack, German photographer Richard Peter entered the city, formerly known as Florence on the Elba for its baroque magnificence, climbed the town hall tower and took this photograph.

II.

By 1960, most of the debris had been removed from Dresden. But rebuilding was slower, leaving large parts of the city as a grid of streets criss-crossing an empty field.

To prevent a forest from growing over the contours of the lost neighborhoods, the authorities kept sheep grazing among the ruins.

It was here, from July 12 to 14, 1960, that Dmitri Shostakovichthe Soviet composer, wrote his String quartet no. 8. It was in Dresden to score Five days, five nights, a film about a German communist who recovers classical paintings from the ruins of the Zwinger palace complex in Dresden after the bombings. But depressed, Shostakovich spent most of his time in a residence reserved for high-ranking members of the East German government, an hour’s drive southeast of Dresden, contemplating suicide in a spa; his hands were affected by an unknown disease that made him. impossible for him to play the piano and his second marriage had just ended; an unhappy marriage into which he had thrown himself immediately after the death of his first wife, the physicist Nina Varzar. The string quartet, written in a three-day burst of energy, quotes melodies from the major works of Shostakovich’s career. He also cites the symphony Tchaikovsky wrote before committing suicide by drinking cholera-infected water. This made Shostakovich’s friends worry.

III.

Unlike symphonies, which require 80 to 100 musicians and a concert hall, quartets cost next to nothing to perform. You just need four musicians and a living room. If symphonies are great publications, quartets are the blogosphere. It is the form that composers turn to when they want to make a work that is too daring or personal to be viable on a large stage.

By 1936, Shostakovich had learned the danger of using large stages to explore his most daring ideas. Then his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk district it was hailed as one of the proudest cultural achievements of the USSR. It had run continuously for two years in Moscow and was being staged in opera houses around the world.

Then Stalin went to see it. Stalin, then at the height of his power, was not above writing opera reviews and one soon appeared in Pravda. It was not signed, but most readers would have known who wrote it, or at least who it spoke for. The editorial called the opera “a real crime”. Shostakovich had thrown dirt in the face of the Russian people. “Things,” noted the editorial, “could end very badly.”

The next symphony, the Fifth, was presented by Shostakovich as a “creative response of a Soviet artist to justified criticism”. It was a markedly more conventional work. He had given in and started living.

But the State was less vigilant in detecting the subversiveness of minor works, such as the quartets.

IV.

String quartet number eight, the Dresden Quartet, was dedicated to “the victims of fascism and war”, and this is partly a cover-up. It was a front that made him agreeable to the State. But the dedication also speaks of a genuine horror that Shostakovich experienced as he walked through the empty fields of Dresden. The composition has several passages that can be read as expressions of the bombings: there are the violin stabs in the fourth movement this sounds like air raid alarms, and there are the Jewish dance in the second movementone of the most intense and gnarly pieces of music I’ve ever heard – it sounds like a firestorm where people are being sucked into burning buildings.

But all the deeper and tacit allusions in the piece point to Shostakovich himself, the self-quotes, the very personal references to other pieces of music and, above all, the motif that opens the composition. This melodic line, D Eb CB, in Russian musical notation is written DSCH, as in: D. Schostakovitch Again and again: DSCH, DSCH, DSCH, more than a hundred times his name appears encoded in the composition.

There’s something touchingly pathetic about repeating your name over and over in a composition. Shostakovich was not a heroic man. He made his music conform to the demands of the state, allowed himself to be used as international PR for the USSR, his name was regularly attached to official statements supporting Soviet foreign policy and expounding the Stalinist doctrine of “socialist realism”. ” When he visited New York in 1949, people demonstrated outside his hotel with signs asking Shostakovich to jump out the window and stay in the West. Shostakovich did not jump. At a press conference in New York, Nabokov asked him if he supported the then-recent denunciation of Stravinsky’s music in the Soviet Union. A great admirer of Stravinsky, a major influence on his music, Shostakovich answered yes. He was dismayed by the state and the terror he unleashed on the population, killing several of his friends, but his defiance went no further than smuggling his initials into his compositions.

When judging artists in totalitarian regimes, it is tempting to elevate dissidents. Solsynitzyn collects the stories of Gulag prisoners and smuggles them to the West. Tarkovsky refused to edit his films in accordance with the demands of the Soviet censors and fled to Western Europe.

But openly challenging the state, like Solsynitzin, was often a death sentence, and Tarkovsky spent the last years of his life consumed by cancer in Paris, unable to reunite with his wife and teenage son, who was held in the USSR. This is too much to ask of a coward like Shostakovich, as it is too much for most of us.

When I hear Shostakovich repeat his name over and over, what I hear is: “I, Dmitri Shostakovich, deserve to exist, in the face of this inhuman terror, despite my cowardice, I deserve to exist.” And at that moment, I feel that I, too, with all my limitations, deserve to exist.

You can listen to it here. Here is the Borodino Quartet’s recording of the piece, and Shostakovich particularly liked his performance:

Once they [Borodin Quartet] came to his flat to play Quartet No 8. When they finished, he was silent for a few minutes. Then he got up and left the room without saying a word. They sat there for a while, and then his wife came and they took their things and left. The next day Shostakovich called Berlinsky and said: “I’m sorry for my silence yesterday, but I was very moved; please, just play as you played.”

I also recommend his version of Shostakovich 15th, and last, quartet.